Doxa has been on a hiatus with billing paused for a while now, as I’m currently attached to another project that I’m not yet talking about publicly. I’m going to try to get the updates coming again, but leave billing paused for the foreseeable future.

Sure, Eric Weinstein, I’ll take a crack at that one, but instead of offering up a name, I’d like to throw my own hat in the ring by offering my own hypothesis. Crucially, my model doesn’t aim to explain why the state of our current world is so bizarre, but rather to unpack why it feels so bizarre in a way that seems to cry out for some grand explanation.

To set up my explanation, I’ll start with a story — actually, a story about three stories that culminate in a fourth meta-story. Here goes:

For whatever dorky dad reasons, my latest thing is that when I pick my kids up from school, I tell them about some random insane thing I saw on social media that day. The first time I did this, I relayed an item from a local Facebook group about a fire at a pet boarding facility up the road that killed 75 pets. (It was a huge local tragedy, and was the talk of the school the next day.)

The next time I did it a few days later, I gave them a detailed recap of a weird ninja attack on a Special Forces group out in California.

Then yesterday, Facebook was basically deleted from the internet for a while, so of course I had to tell the kids about that.

I selected these stories for engagement — to have something stimulating to talk about with the kids in the truck. And it definitely worked. All three of these items were hot topics that occupied us for the rest of the ride home.

But the post-Facebook-downtime conversation was different in an important way from the other two conversations. The kids were engaged as usual, but this time they did something odd: the moment I broke the Facebook news and their brains had a second to process it, all three of them immediately began talking over each other to spin fantastical stories about a shadowy clan of ninjas who had set fire to the Ponderosa Pet resort, assaulted a Special Forces team, and then taken out Facebook.

They were sort of joking, in that way that kids do when they’re like, “I’m just spitballing this really cool thing but it maybe it’s real because it would be awesome if it was!” But what was wild was the way they all three spontaneously made the same move of putting these three random items together at the same time in roughly the same way.

I know why they did this, because lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the mechanics of why people are building outlandish worldviews out of wild speculations and connections on social media, and why the world feels “rigged” or “scripted” to so many of us nowadays.

Text and context

It’s often alleged that social media feeds us news stories stripped of context. Like I do with my dad news updates in the car ride after school, social media’s critics observe that the platforms select stories for engagement, then flatten them down into a standardized post format with an excerpt and a hero image, then put them in front of us in a feed that strips them of the kinds of context we need to make proper meaning.

But this picture isn’t quite right. The items and events in our feed are not devoid of context — on the contrary, they’re absolutely loaded down with it. Smothered, constricted, pressed, smashed, and warped into context by the pressure of an intensely powerful, industrial-scale context-generation machine.

To return to my truck again, all three of my unconnected dad news items were delivered at the same time of day, in the same location and surroundings, with the same vibes, in the same voice, etc. In other words, all three stories shared the same context, i.e., “a random event dad told us about when we were in the truck coming home from school, driving along the same route at the same time of day, and offered with the same dad delivery.”

So despite the fact that I made no particular effort to give any special context for any of these stories, the kids nonetheless consumed them with loads of very powerful sensory context. And because that context was identical for all three stories, they naturally interpreted the stories as having some connection — they interpreted these three discrete stories in light of one another.

To drive home the point home that the uniform packaging, delivery, and consumption of news items provides a powerful, natural context that encourages an audience to interpret a sequence of engagement-optimized stories in relation to each another as a part of a connected unity, and to construct a single story out of them, bear with me on this whole truck thing for a moment longer to entertain the following counterfactual.

Instead of hearing about these three news items in my truck on the way home from school, imagine if my kids had encountered them in the following ways:

They heard about the Ponderosa Pet Ranch fire from their teacher at school, whose friend lost three dogs in the fire. (Their teacher’s friend really did lose three dogs in that fire.)

They learned of the ninja attack in a news item on the radio, which they sometimes listen to in their room.

They heard of the Facebook hack from their mother, who had been trying to get on Facebook and couldn’t.

If the above had been the case, would they still have joined these three news items together into a single story about pet-hating arsonist ninja hackers? Very doubtful.

Reality, tokenized

To understand what the web’s structuring of reality as a feed of uniformly formatted, deliberately stimulating content items is doing to our individual and collective meaning-making capacity — and I don’t just mean social media, but every modern news delivery vehicle, from news websites to apps to social networks — we can reach for a concept that has lately blown up via crypto: the token.

Wikipedia gives us a number of definitions for “token,” and of course an on-chain token is its own particular thing. But I want to veer into slightly crypto-adjacent territory by talking about lexical tokens.

When a computer is trying to make sense of a string of text — a compiler is trying to parse a computer program’s source code, MATLAB is evaluating a mathematical expression, or a natural language processing algorithm is translating a phrase from French to English — it begins by breaking that text up into a sequence of tokens.

These tokens are basic units of meaning that are interpreted in light of their immediate context — the order and arrangement of tokens (usually) matters for interpreting what both a particular token in a collection and the token collection as a whole is supposed to mean. Here’s a sentence in English broken up into parseable tokens, where the token boundaries are marked by spaces and punctuation.

To steal an example from the philosopher of language John Searle, let’s append a few more tokens to the end of this string and watch the story take a sudden turn:

To summarize, a token has the following salient qualities for our purposes here:

A token’s format is standardized in some way. I.e., all the tokens are assembled from the same symbol library, and they have a standardized set of boundary markers (spaces, commas, bounding boxes, etc.), and there are rules that govern their possible arrangements.

Tokens get much of their meaning from their selection and arrangement in a medium, e.g., words on a page, lines of code, numbers in a spreadsheet. This is a fancy way of saying that a token’s immediate context matters.

Following the above, tokens are interpreted in terms of each other. Just one token in isolation doesn’t tell you very much — you need to look at a sequence of tokens to make sense of both the part (the individual token) and the whole (the token sequence). (If you want a ten-dollar grad school word for this part <=> whole movement, it’s the hermeneutic circle.)

The above stuff about tokens uses specialized lingo, but it’s not some specialist idea — I’m not using computing as a metaphor for the brain here. Rather, it’s a basic philosophy of language and philosophy of mind thing. We interpret words (written and spoken) with reference to the words that come before and after them. We interpret events with reference to events that come before and after them (diachrony), or that occur simultaneously to them (synchrony), or that occur nearby in space.

We also tend to draw lines between “same” and “different,” grouping like things with like things in order to make sense of them. Appearance and format matter, ad are a crucial part of context.

Strip away all the talk of tokens and hermeneutics, and my point is straightforward and obvious: context is powerfully linked to proximity and visual presentation. The closer in time and space A and B are to one another, the more likely the conscious mind is to interpret A in relation to B, and vice versa. The more A and B look like one another, the more likely we are to infer that A and B belong together and share some connection.

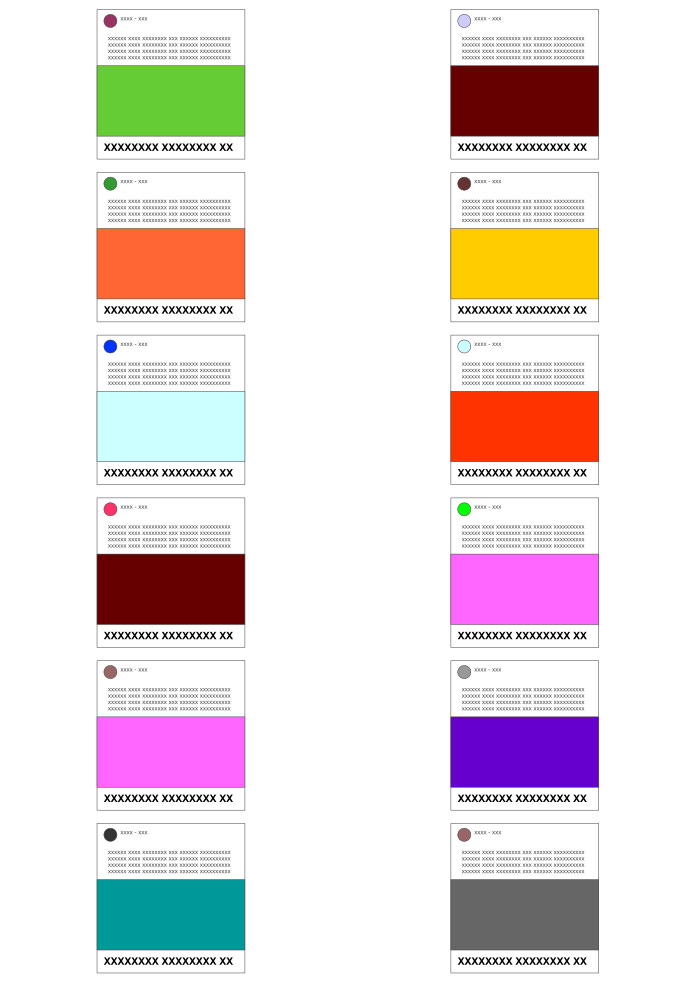

Now let’s look at an abstract rendering of a news feed. It could be any feed, from a social media feed, to a sequence of Substack posts, to a Google News or Apple News page, or whatever. Imagine that these are all news items, memes, shower thoughts, opinion pieces, etc. that some algorithm estimates will stimulate and engage you.

Stare at that for a moment, and then I’ll give you the main point of this essay: that ordered sequence of items in the above diagram presents as a sequence of tokens all in proximity to one another, and our brains are wired to interpret those tokens in relation to one another. We take meaning from these tokens’ selection and arrangement as discrete units, and thus we interpret the feed the way we interpret any collection of proximate tokens that have been assembled off-stage somewhere and presented to us.

Filter bubbles and the simulation effect

The web’s clean formatting and tokenization of the world’s day-to-day happenings has a few implications for how we make sense of reality.

First and most obvious is the simple fact that the body of larger narratives an individual pulls from “the feed” depends greatly on the peculiar composition and arrangement of the token sequence being shown to that person. We may all see the same ten major news stories or social media dramas on a given day, but the actual token sequence that carries this information to us is very different for each individual; I think this subtle wrinkle matters a great deal more than we acknowledge.

One person’s feed is sequenced one way and another’s is sequenced another way; so those people inhabit two different worlds of meaning because the highly charged feed of VERY IMPORTANT tokens, which is the reality many of us live in for some 8-12 hours a day, is arranged a bit differently (or a lot differently, in many cases) for each person.

(What I’m describing is, of course, the much-remarked-upon filter bubble. But I think my account extends the concept a bit, in that it adds order and proximity alongside the selection of items as important factors in bubble construction.)

Second, I suspect the active human and algorithmic curation of these token sequences is what gives rise to what I’ll call the simulation effect. The simulation effect is that feeling, often expressed on social media, that there’s something off — that reality is rigged somehow. As Morpheus put it in The Matrix: "What you know you can't explain, but you feel it. You've felt it your entire life, that there's something wrong with the world. You don't know what it is, but it's there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad."

The regnant joke of the age is, “the writers are too on-the-nose this season.” The simulation effect is that weird sensation that somehow everything that’s going on is being scripted in a writers’ room somewhere. The widespread nature of this feeling has got to be behind the perennial popularity of the simulation hypothesis.

Newsflash: If you’re spending 8+ hours a day in front of a feed, then that feed is “reality” or “real life” for you; and if that feed is reality, then reality is rigged because the feed is rigged. Again, the feed isn’t some window on reality — it is reality. You’re not interacting via your feed with, say, a wildfire that’s happening out there in reality somewhere; you’re interacting with a feed item about the wildfire, and that feed item is a thing that’s in your reality on that day that you came across it.

So yes, Very Online Person, your reality is indeed being rigged by a process of tokenization, curation, and consumption — all with the goal of keeping you engaged in constantly parsing that token stream via what amounts to an ongoing DDOS attack on your natural sense-making apparatus. The relevant -ation here isn’t simulation, but stimulation.

Like my kids in the backseat of the truck, you’re getting a sequence of engagement-optimized, uniformly packaged tokens from the same screen in the same day-to-day environmental and sensory context, so no matter how tech-savvy you are, your nervous system is going to insist that all of these things are somehow related to one another and that you can uncover the pattern if you just keep reading. Your evolutionarily optimized meaning-making module is destined to keep trying to stitch this wild, sparkly cluster of apparently related tokens into the plot twists and turns of a handful of larger stories. How could it not?!

What’s worse is that the smarter you are, the more adept your brain is at building connections between pairs of tokens that strike lesser minds as unrelated to one another, and the more pleasurable you find this synthesizing activity. The feed, then, is especially dangerous for smart people, because of the way that its tokenization of information primes their exceptionally capable inference machinery. And smart people, in turn, are dangerous for dumb people, who swallow whole the smart people’s clever readings of the feed’s tokens. (Smart people have always been dangerous for dumb people, so this part, at least, isn’t new.)

To be clear: the simulation effect — the sense that reality is rigged — isn’t happening because the feed algorithm is telling you an artificial story that it constructed for you; rather, the feed algo is structuring your reality in a tokenized and sequenced form, and you’re reading and interpreting that collection of tokens by doing what humans naturally do with collections of tokens (i.e., interpret them in relation to one another and fit them into some kind of story). The feed isn’t making the story — it’s making your tokenized reality, and you’re making the story out of that wonderfully titillating token collection the feed has assembled for you.

What to do about it

So far, I’ve described a particular direction that the feed operates in: happenings in the world are pressed into tokens, those tokens go through a selection and sequencing process where they’re turned into feeds, and those feeds are turned by communities of readers into a set of (increasingly bonkers) stories about the world and how it all really fits together.

But there’s a feedback loop at work here, and in the next installment, I’ll close it. To preview: people take the stories that either they or someone else pieced together from the feed’s tokens, and then they go data dredging in the indexed sea of tokens that is the web for supporting context, which they inevitably find in abundance. But more on that, later.

As for what to do about this, I have no idea. Not only are we not going to un-tokenize our online reality, but we’re going to keep moving in the opposite direction. More things will become digital, and more things will become tokens — especially the parts of our world that go on-chain.

So there will be more tokens everywhere you look, and more things will be explicitly called tokens. Right now, Bitclout lets you mint a token from a clout. News stories will get minted as tokens. Tokenize all the things.

I hope that by clearly naming the forces at work, and by being intentional in how we design software, we can engineer our way around some or all of the problems I’ve tried to describe here.

Observant readers will also note that most of the claims I’ve made in this post are pretty easily testable. This stimulation hypothesis shouldn’t be too hard to test by designing an experiment to measure the degree to which the tokenization and sequencing of information affect our interpretations of events and our propensity to make connections between unrelated items. So whatever we do about any of this, the first step would be to try to measure it and then to revise any of the above claims that don’t stand up to experimental scrutiny.

I also think there may be some hope in the metaverse. The tokens there present differently, so there’s likely an opportunity there to make these problems either a lot better or a lot worse, depending on our approach.

I don’t use social media apart from fb to occasionally post photos of my dog and/or kid. (I still don’t understand the attraction of twitter or instagram.)

As for what to do about it… while my undergraduate degree is in physics and computer science my graduate degrees are in history and law, which I found extremely fulfilling. I recommend reading more history. The context that learning about history provides is (IMHO) invaluable.

Well put. Sometimes the medium DOES form the message. Comments: To prevent total absorption into the matrix during peak 2020, I imposed a sanity filter. On any given day I'd just unplug, sit outdoors looking at the trees, sky, animals etc. just to remind myself that all of reality was not contained in The Feed. Likewise, I found it helpful to filter the feed by unfollowing, blocking or muting all those that I knew had obvious agendas that would hinder the flow of info useful for living my life in the real world at the time. (This included those aligned with my own politics) Which leads me to an observation and perhaps advice: I think many see their feed choices as unchangeable rather than something that can/should be adjusted. Soc. media can, ( I would say ought to) be used like a telescope on a tripod: Able to change focus and direction and to be able to adapt to the current issues that are relevant to you. If North Korea is an issue you change direction to deliver that info and block out all else. (Same with pandemics, wars, elections etc.) Make the feed fit your needs, not the other way around. There is a spoon. Be brave, bend it to your will. (Yes, I know this is not as wonderfully meta as your observation but it helps to remind ourselves that we do have the ability to make changes, even to The Feed.)