Anti-Stable Diffusion Lawsuit Deep Dive: It’s A Neutron Bomb

The endgame is to eliminate the artists but leave the servers running & churning out animated features.

The first major lawsuit against Stability AI has arrived, and the different AI art channels I follow have been furiously debunking the suit’s technical claims as they’ve been published by the lawyers. That debunking is all well and good — I’ve indulged in a little of it, myself — but I’m not sure most of the community really grasps what it would mean for all of AI if a court were to swallow these claims and make them the law of the land.

We AI nerds can all snort and guffaw at these lawyers’ leaps of logic and errors of fact and interpretation, but if these bad arguments win in court then they will have dire implications for every aspect of the machine learning-drive software boom that we’re in the very earliest stages of.

(I have a new piece out in Reason that goes into some of the implications of this lawsuit for artists and for machine learning, but I couldn’t fit everything in there. So consider this a companion piece to that one.)

Here are the class action complaint’s three most important claims, as I understand them:

The Stable Diffusion model weights file is a derivative work (from the standpoint of copyright law) of all the copyrighted works in its training data set.

Every AI-generated image is legally a derivative work of the model’s copyrighted training data.

Style transfer actually doesn’t exist — at least not as it’s normally understood by ML researchers, where a model creates a totally new, unrelated work in the general style of an earlier one. Rather, what ML says is “style transfer” is actually “collage,” in that it’s just an automated copy-paste of the literal pixels and lines from a set of (copyrighted) predecessor images.

There are other claims in the complaint about web scraping, and whether Stability AI lawfully accessed all the images, and so on. I don’t expect that stuff is really salient though because otherwise, Google is in big trouble. The above two arguments are the real core around which the rest of the suit is built.

And by way of laying out the stakes up-front, here are the main implications of these three arguments:

Following on #1 above, anyone who profits from the model weights file — i.e., Stability AI, software makers who are using the model in their code, creatives who are using the model to generate commercial work — is profiting from a derivative work and owes the owners of the training data’s copyright a cut.

Following on #2 above, a small-time or independent creator could just never use any AI-generated image commercially without serious legal risk. Only the big IP rights holders would really be able to use such images because only they are protected from litigation by their size, deep portfolio of IP, and a network of licensing arrangements that amount to big incumbents promising not to sue each other.

Following on #3 above, if I were to use Stable Diffusion to make a picture of my face in the style of a Pixar movie, then I have created a derivative work of Pixar IP. So Pixar would have an enforceable copyright interest in that style-transferred image and could sue me for using it commercially. (If I used Photoshop to make this same image, it would not be a derivative work and I could therefore do whatever I like with it, including selling it.)

My Reason piece focuses on the implications of #1 above — the alleged status of the Stable Diffusion weights as a “derivative work” — so I’ll focus more on #2 in this piece when it comes time to think about what this lawsuit might mean for all of us.

But before I get further into the suit and its implications, we have to talk about the law.

Derivative works

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer. I’m just a guy who’s been writing about copyright and other IP issues online for twenty-five years, which means I know just enough to be dangerous. Nothing in this article is legal advice, and no lawyer has vetted any of it. If you’re a real lawyer in this area and you spot a mistake in any of what I say here, please reach out and so that I can correct it.

Derivative work is a legal term that essentially means: a work that it’s in some way derived from an earlier copyrighted work. The US copyright code’s definition of this term is actually pretty readable, so I’ll quote it in full:

A “derivative work” is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a “derivative work”.

For our purposes here, there are two things that are important about the bit of law above:

It doesn’t explicitly discuss the tools you used to make the new work, or even the medium or format. Photoshop software, sidewalk chalk, interpretive dance, whatever — if the end result contains elements of a pre-existing, copyrighted work, then it’s derivative no matter how you produced it.

It doesn’t have anything to say about the vague, I-know-it-when-I-see-it abstraction that is an artist’s or studio’s signature “style.”

The main reason I bring up that first point about the tools is that when many of us talk about Stable Diffusion there’s a lot of slippage around whether the model is a “tool” or a “creator” in its own right. I personally am quite guilty of this, because as much as I write and think about how both my own brain and generative AI models are “black boxes” (at some important level of abstraction) and could be doing the same kinds of creative things, when it’s convenient for me I refer to generative AI as a mere software tool on par with Photoshop.

This slippage is natural with something this new, where we’re all still struggling to figure out what we’re dealing with here. But for the purposes of talking about this lawsuit and rebutting its claims, we need to be clear: the lawyers are arguing that Stable Diffusion is merely a software tool, is not creative in its own right, and cannot possibly, under any circumstances, produce any work that qualifies as wholly new and completely original.

As for the second point about style, hold that thought, because we’ll come back to it in a moment.

Goal: platforms must treat all AI art as digital contraband

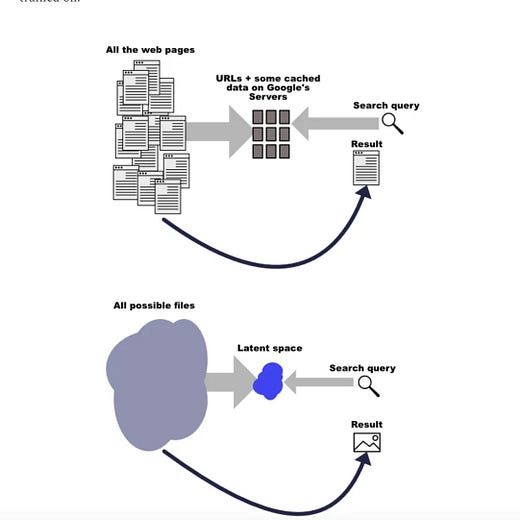

I want resummarize the compliant’s position for emphasis: by definition and owing to how these models are constructed, absolutely nothing that you get out of Stable Diffusion (DALL-E 2, or Github Copilot, or ChatGPT, or any other LLM) in response to a prompt is a completely original work from either a philosophical or a legal standpoint. Not a thing.

This idea is elaborated on at length in the complaint and supported by numerous (bogus) technical claims and tortured metaphors, but here it is early on in the document, on page 3:

“Derivative Work” as used herein refers to the output of AI Image Products as well as the AI Image Products themselves—which contain compressed copies of the copyrighted works they were trained on.

Per the arguments in the complaint, every arrangement of pixels in a Stable Diffusion-generated image is derived directly from a copy of part or all of a previous work that exists in the training data. It is a “digital collage” tool, they insist, and all it does is use statistics to cut, paste, and rearrange parts of human-made images.

The legal implication of this stance is that when you make an image with Stable Diffusion, you are always, 100 percent of the time, in every instance, without exception, creating a derivative work from someone else’s copyrighted material.

So this image, which I created from Stable Diffusion 1.5 with a random seed and the text prompt as;lkjasdf;lkjasdf;lkjllallskdksad2341234-908, is not noise or random pixels but is in fact a derivative work that is derived from multiple copyrighted works in the training data.

If I wanted to sell that image, then I would first need to identify all of the images in the billions of training images that the model allegedly cut and pasted together to produce the image above, and then get permission from every one of those rights-holders and possibly pay them a royalty.

Obviously, this is preposterous and completely impossible, because the model is not cutting and pasting anything, and even if it were (again, it isn’t) I’d never be able to identify the source images. So I essentially could never safely sell that image… which is exactly what the folks behind this lawsuit want.

If an image is produced by Stable Diffusion, then the lawyers want the law and the tech platforms we all use to treat that image presumptively as a derivative work where the rights holders whose work has been used to make it have not given their permission to whoever’s using it.

This can and will mean a lot of things in practice, but one immediate effect is that every media outlet that has been using Stable Diffusion-generated images as hero images in their articles is going to have to remove them or expect a legal shakedown.

The other effect is that nobody outside the big content houses, which have the deep pockets and vast portfolios needed to protect themselves from lawsuits, could use safely generative AI in a commercial capacity. For every image you produce, you could expect that some rightsholder whose work appears in the training data might come calling with a colorable legal claim that your image is somehow derived from theirs. In this world, generative AI would be the sole province of Big Content.

I didn’t think of this metaphor in time to squeeze it into the reason piece, but as far as independent artists and creatives are concerned, this lawsuit is a neutron bomb: it will kill the artists and leave the servers and algorithms running, so that future Walt Disney Company hires no artists and staffed entirely by some technicians who maintain a server farm that generates profitable content 24/7.

As I put it in Reason:

Disney would be able to work with Microsoft, OpenAI, Google, and other big tech platforms to use these large, closed-sourced models to replace the teams of artists they currently employ. They could fire most of their talent and replace them with A.I. that cheaply generates infinite new content from their vast catalog of existing intellectual property. Meanwhile, independent creators and noncommercial users would be prevented from using these same software tools to compete with the Disneys of the world—they'd be stuck in the era of making art the old-fashioned way.

That seems to be what the plaintiffs in this suit want. But I don't think they fully realize what it would mean for them if they left all the generative A.I. solely to Big Content.

Goal: automated style transfer is effectively impossible

As I’ve pointed out in a previous post, it’s not really possible to copyright an art style. It’s often hard to define what a style is, even, but for artists and studios that have their own signature style, most people can spot it on sight and many artists can imitate one style or another.

But if the class action suit against Stable Diffusion is successful, an artist or studio will effectively be able to sue someone for using Stable Diffusion to imitate their style.

For instance, the image below was created by a Playground user and is a little tortoise done in the style of a Pixar movie.

Unlike, say, the SD-generated Spider-Man images in my Spider-Verse 2025 post, there is zero copyrighted content in this picture. There is a juvenile sea turtle in Finding Nemo, but it’s not this one, or even a tortoise like the one in the picture.

So if Playground user Derek Sokol had created the above image with Procreate, everyone — including, presumably, the lawyers behind this class action complaint — would agree that it’s a totally original work completely unencumbered by any copyright interest other than Derek Sokol’s.

But it was created by Stable Diffusion, and there are images from Pixar movies in the Stable Diffusion dataset, and the word “Pixar” is in the text prompt. So by the clear logic of this complaint, the above image is a derivative work and Pixar has a copyright interest in it. If Sokol wanted to make commercial use of this image, he’d have to get Pixar’s permission first.

Again, if he had created it by hand, he’d be in the clear. But because he used Stable Diffusion and the lawyers claim Stable Diffusion is a “collage tool” that can only create derivative works, Pixar owns part of that image.

In a world where these lawyers have their way, style transfers done by generative AI are not worth doing if you’re going to use the work commercially, because you’d have legal exposure.

Stochastic terrorist parrots

This document draws on two main sources for assembling its explanations of what generative AI is and is not doing:

The metaphors, intuition pumps, analogies, and explanations that I and many others have marshaled in service of helping people reason about (and develop productive intuitions about) how AI works.

The criticisms of “AI hype” offered by Timnit Gebru, Emily Bender, Gary Marcus, and numerous others who are on a crusade against large language models (LLMs) as dangerous, overhyped, and in serious need of reining in.

I’m seeing the search query language I used in my intro to generative AI come up in there a lot, as well as a few other concepts that feel nauseatingly familiar to me. I’m not sure if they’ve drawn this stuff from my Substack, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

But here’s the deal: I do speak of text prompts as search queries, and I do speak of machine learning as a form of compression. (Indeed, I have an unpublished draft that’s solely dedicated to talking about ML as compression and unpacking the implications of that for computing.) This is all good, and I’m going to keep doing it, but I and everyone else has to be aware that these concepts are now being abused and misused by lawyers to smother generative AI in its cradle.

They are going to draw on work and concepts from ML researchers and those of us who are just trying to educate and advance the field, and they’re going to turn all that on us. So we have to keep doing what we’re doing, but be prepared to answer the call to push back with nuance and truth.

As for my second point above, this class action complaint can very fairly be said to be a direct sequel to Gebru, Bender, et al’s infamous “Stochastic Parrots” paper. Exactly like the paper that played a pivotal role in Gebru’s separation from Google, this document argues that generative AI is merely using statistics to parrot its input data, and that this stochastic parroting is incredibly bad and dangerous and should be stopped before gets out of hand.

There’s a whole other essay I could (and probably should) write about how blog posts like this, which purport to be all about fighting hegemony and sticking up for the marginalized, are really just turning out to be useful idiocy for the most powerful and entrenched interests in the modern world.

But for now, I’ll leave it at saying I hope Gebru, Mitchell, Bender, and all their hangers-on who are keeping the “Stochastic Parrots” discourse alive, read this complaint thoroughly and think about what their arguments are being used to support.

There's several fundamental fallacies in your argument here:

Firstly, "AI" is a very strong word for the algorithmic lovechild of blind watchmaker programs and image compression. There is no actual thought going on there, simply an impressively efficient (if rather lossy) database with an integrated search engine/parser attached to it. This itself is an impressive innovation- the genetic algorithms here have found a way to render down images to a form can be easily stored and then reconstituted in a useful way.

That leads us to the second main issue- Describing what these neural networks are doing as cutting and pasting is a straw argument. The actual process is more complicated, more akin to a very fancy mixture of tracing, texture interpolation, rotoscoping, and what artists call photobashing. Photobashing involves the manipulation of existing images as a foundation for another work, the name derived from the crudest form involving "smashing images together" like a collage to create a composite image. The more advanced form involves painting over top of an existing image or collage of images, drawing forms, textures, and colors from this base. It can make for very impressive-looking results but is easily spotted by an experienced artist who knows what they're looking for- and it has an infamous dark side where many artists have been caught using photos under copyright or other artist's works instead of personal or properly licensed stock. These programs blatantly do exactly this in ways that are extremely obvious to an artist's eye, even with the stable diffusion algorithm's data storage format inherently helping to disguise this sort of image stitching.

That leads into the third problem- It may not be literally tracing an image, but when a program uses minor variations of the same silhouette for every image of a horse it produces there is clearly a template it has distilled from its input. If the template was created by tracing many works and averaging them together, that makes it worse, not better- its creator has simply had it carry out automated plagiarism many times.

We artists object not because this is something new and scary, but a sort of fraud we are very familiar with in a new form.

I disagree with pretty much everything. Emad himself declared Stable Diffusion to be art history compressed into 4GB, and 'cut n paste' is mentioned nowhere in the complaint. It constantly states SD as a *new form* of collage tool, which is essentially what it is, except the collage bits have been atomized into postmodern grey goo, which you can morph into new forms by prompting.

Regarding webscraping: You do know that Google settled with Getty Images and had to make all kinds of adaptions to keep their image search, right?

I don't think that any of your arguments have merrit in court. As i wrote in my Substack: https://goodinternet.substack.com/p/the-image-synthesis-lawsuits-cometh

The only thing that matters here is if the companies involved used unlicensed artworks in the creation of a commercial tool, and if the Fair Use defense applies to a machine that can mimic artistic style.

They did, and we'll see.

update: Oh, and you totally didn't mention the paper that proved that SD can put out training data verbatim: https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.03860