Crypto reaps the whirlwind

Treasury moves against Tornado Cash

On Monday, a dramatic law enforcement action by the federal government sent a big chunk of my Twitter feed into ron_paul_its_happening.gif mode. Accounts were warning darkly of a major ramp-up in politically motivated persecution, urging their followers to prepare for war.

No, I’m not talking about the raid on Mar-a-Lago. Rather, I’m talking about the US Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) move to sanction Tornado Cash, an on-chain application for anonymizing cryptocurrency flows.

Some of my audience is deep into crypto and knows exactly what just happened and what it means. But for the many who are watching from the sidelines and scratching their heads, what follows is an explainer to get you oriented.

I’m posting this explainer because this development is kinda huge, and it matters a lot. To further extend the implied right-wing analogy from my opener, this may be something like crypto’s Waco or Ruby Ridge. It’s important for the non-crypto-pilled in my newsletter’s audience of media, academics, and researchers to understand what has just happened, and what the stakes are for crypto.

In brief:

The blockchain’s public nature means that unless the chain is deliberately designed to thwart scrutiny (most are not), anyone can examine the public ledger to trace the flow of funds from one account to another.

People who want on-chain privacy for whatever reason — ideology, crime, political persecution — can use “coin mixers” that tumble their transactions around with those of random strangers in order to make it difficult for anyone to untangle what coins actually went where.

If you know what Tor is, coin mixers are a similar idea — i.e., a means of intentionally obscuring information flows by having complete strangers, selected randomly, route each other’s traffic around a public network.

Tornado Cash, which was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department, is one such coin mixer, but there are others that operate on other blockchains.

Tornado Cash runs on Ethereum. Its implementation is just a bunch of smart contracts written to the blockchain. So unlike with Whirlpool and other coin mixers, there’s no server or group of servers that actually runs the software. Or, rather, you might say that every Ethereum node is running Tornado Cash because its code is part of the public blockchain now.

Because there’s no server, and therefore no hosting provider or other infrastructure to target — the US government has sanctioned a list of Ethereum addresses where the contracts that make up Tornado Cash can be accessed.

The bottom line is that the government is sanctioning a set of numbers that don’t belong to anyone and aren’t controlled by anyone, can’t be shut off by anyone, and are accessible to everyone.

This may sound insane, but, y’know, welcome to crypto.

The no-touch rule

What does it mean for the Treasury to sanction a set of numbers that correspond to smart contract addresses on a public blockchain? Well, this is something that everyone is furiously trying to figure out because the details matter a lot.

As near as we can tell, it seems that any party that’s caught interacting with one of the sanctioned addresses on-chain — and by “interacting” I mean sending crypto to it or receiving crypto from it — is in big trouble with Treasury. The way these OFAC sanction rules are written, neither innocent intent nor ignorance are valid excuses. Get caught touching those addresses with your own wallet, and you have instant legal exposure.

Now, tuck this “no touching the sanction addresses for any reason, no matter how innocent” rule in the back of your mind for a moment, because we’re going to come back to it shortly.

Wallets, smart contracts, and permissions

Crucially, this isn’t the first, second, or even third time Treasury has sanctioned a list of blockchain addresses. This practice of sanctioning addresses associated with bad actors goes back to at least 2018. But as far as I know (someone correct me if I’m wrong), all of the addresses sanctioned before Tornado Cash have been simple wallet addresses — not smart contract addresses.

For the non-crypto-pilled, here’s why the above distinction matters. A wallet address is under the control of whatever entity (a user, a computer program, even a smart contract) has control of that address’s private key. You need the wallet’s private key in order to move funds from it. So if I have a wallet address and its corresponding key, I am the only person in known universe (at least, according to our current understanding of mathematics) who can move funds from that address to another address on the blockchain.

However — and this is critical, so don’t skip this part — anyone who has my wallet address can send funds to my wallet, and I cannot stop them. There’s just no mechanism in the blockchain for refusing funds (or, in fact, NFTs or other crypto assets) from an address that wants to send them to you.

For instance, my ENS name is jonstokes.eth, and it resolves to 0x375C12259aa3001e4Fd7f3f5739061Df7A13F31f on Ethereum. That means that if you want to send Ethereum to that address, then I cannot prevent you from doing that.

Payable smart contract addresses have a lot in common with wallet addresses, but unlike wallet addresses, the flow of funds out of a smart contract is governed by the smart contract’s code. When you call a payable smart contract with some funds, it will execute in the Ethereum Virtual Machine and do whatever it was programmed to do with those funds. In the case of the smart contracts that make up Tornado Cash, you tell the contract where to route your funds, and it does all its mixing and then makes sure that your funds get where they’re going. No human has to intervene for this to happen; it’s automatic, and in fact, no human could stop it if they wanted to, short of shutting down the entire Ethereum network somehow.

So US Treasury can’t turn off Tornado Cash without turning off the entire Ethereum blockchain, and given that Ethereum is global and decentralized, it can’t be turned off by any one party short of turning off modern computing and civilization.

I’ll pause for a moment because I want that to sink in: this is a piece of global financial plumbing that the almighty US Treasury cannot turn off, stop up, or otherwise disable. This technology runs on a mix of advanced cryptography and human greed, and no power that we know of can stop either of those forces from working in the world.

Legal exposure

Now it’s time to circle back to the “no touching the sanctioned addresses” rule because at this point you’re equipped to spot the problem. If some jerk hates me and wants to get me in trouble with Treasury, he can send some ETH to my jonstokes.eth address via Tornado Cash, and I am instantly exposed.

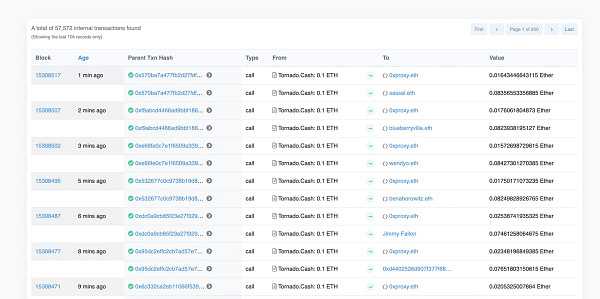

This very thing is, in fact, happening as we speak to prominent crypto accounts with public ENS names. Some joker is sending all these accounts 0.1 ETH, thereby putting them in violation of the letter of the Treasury action.

How bad is the legal exposure of the unfortunate recipients of these tainted coins? Nobody yet knows.

Centralization strikes back

The Treasury’s sanctioning of Tornado Cash wasn’t the only way the hammer came down. A few other things happened, each of them bad in its own way:

The GitHub repo for Tornado Cash was taken offline, and the accounts of its developers were suspended.

The two main crypto infrastructure providers (Infura and Alchemy) that are the main way that most developers actually interact with the blockchain have cut off access to the affected addresses.

Circle, the party behind the USDC stablecoin, has frozen coins held by wallets that have touched the Tornado Cash addresses so they can’t be moved.

There will be more shoes that drop in the coming days.

In short, every centralized piece of the crypto ecosystem has been weaponized against Tornado Cash.

Implications for crypto and for governments

I don’t pretend to have a full picture of what the Tornado Cash moves mean, but I can offer the following mix of observations and reasonable inferences.

The whole crypto ecosystem has gone into a wartime footing over this. If there’s a person in crypto who didn’t know they were at war with the US government before, they know it now. This is the proverbial bloody horse head in the bed moment for crypto.

The VC-funded portion of the crypto ecosystem will keep playing nice with the government because they have to, but the epicenter of the energy in this space will move into more privacy-preserving technologies and tools.

Crypto is global, and the vast majority of its potential users are the billions of smartphone owners who live outside the US. They will keep using Tornado Cash and other mixers, and in fact, there are still funds flowing through Tornado Cash.

Everyone needs to meditate on the fact that the US government has neither the technical nor legal means to shut off this bit of global financial plumbing. Nor does the CCP, or another other government on earth. They can make it difficult or treacherous for their own citizens to use some computer code to touch a specific set of numbers that no one owns and no one controls, but they can’t stop the rest of the world from touching those numbers.

I think the above is a constraint on governmental power that has not previously existed in the human experience. Sure, you can point to gold or cash or whatever, but scale and frequency matter in all things, even financial flows. Trying to stop a few billion smartphone users from accessing a computer program on a public, peer-to-peer networked, singleton state machine that nobody can turn off, is different than controlling the flow of gold or cash. It’s also different than stopping spam, porn, or even speech. We’re in terra nova, here.

One possible implication of the previous point is that governments that succeed in shutting down crypto may only succeed in trapping their citizens in a kind of financial North Korea — a hermit kingdom cut off from the rest of the world. It all depends on how many other countries see crypto as a way to advance their own interests vs. playing along with the West’s financial dominance.

Yes, it’s true: like cash before it, crypto is an enabling technology for all manner of crimes in the modern world. But some of the crimes it enables are crimes of thought, speech, religious belief, ethnic identity, or political activism. Many of us (though by no means all, even here in America) want to enable the latter category of crimes because we believe such things should not be criminalized.

Finally, the biggest lingering question on everyone’s mind is, where does this stop? Why not sanction all the addresses on a blockchain? Or an entire protocol? And if we’re sanctioning math, why stop at cryptocurrencies?