Tom: “So, Greg, listen. I’ve just had a meeting with my private attorney, and it seems I have been exposed to a virus.”

Greg: “Oh… right.”

Tom: “It’s a deadly virus, and now… laughs Now I’m f**ked! Forever!”

Greg: “Sounds bad.”

Tom: “It is bad. It is! I kinda need to share, but anyone I talk to… anyone I talk to, I effectively kill.”

Tom gestures to a blue folder on his desk.

Tom: “That’s the death pit, Greg. Take a look.”

There’s a great scene in the first season of HBO’s Succession, in an episode called “The Death Pit,” where newly promoted executive Tom Wambsgans explains to the hapless Cousin Greg that his predecessor at Waystar-Royco has transmitted to him a kind of deadly virus. This “virus” exists in the form of damning revelations about the firm’s past shady business practices, practices that any employee is legally obligated to report to the authorities the moment they learn of them. Such whistleblowing would, of course, bring down the company, and with it the whistleblower’s career. So it’s a no-win situation, and the only safe thing is to never learn the information in the first place.

Partway through the scene, Tom switches metaphors from “deadly virus” to the “death pit” from which the episode takes its title. Gesturing to a folder sitting on this desk, he says, “That’s the death pit, Greg. Take a look.” Of course, the moment Greg takes a look into the death pit, he’s in it with Tom. As I said, mere exposure to the information in that folder is enough to instantly confer on the reader a career-ending level of legal liability.

I was reminded of this as I watched my feed try to come to grips with the implications of the US Treasury’s recent Tornado Cash sanctions. I explained in a previous article about the no-touch rule — anyone sending Ethereum to the sanctioned addresses or receiving it from them is automatically in violation of the sanctions. The sanctioned addresses are a kind of “death pit” on the Ethereum blockchain. That death pit will be there for as long as the Ethereum blockchain is in operation, but as with Tom’s blue folder, the whole game is to not fall into the death pit by exposing yourself to illegal information. You gotta not open the folder.

But what if you have to open the blue folder? What if you can’t say no?

One concern that emerged very quickly on my feed and has persisted in recent days, as different thinkers wrestle with it on Twitter, is: can Ethereum miners (or, post-merge, validators) accidentally fall into the Tornado Cash death pit merely by adding new blocks to the Ethereum blockchain?

In other words, certainly individual users of Ethereum can fall into the death pit by either sending ETH to a sanctioned address or receiving ETH from one. That much seems clear. But what about US-based miners or validators who add new blocks containing transactions to or from the sanctioned addresses?

If you’re in the US and you’re running an Ethereum node, and someone, somewhere (maybe they’re in a non-extradition country and don’t care about US law) sends to the network a valid transaction that touches one of these addresses, and your mining rig successfully includes that transaction in a newly mined block, did you just break the law?

It kinda seems like maybe you did, doesn’t it? You’re the winner in the contest that added the offending transactions to the chain, so it’s kinda your fault they’re there — you facilitated these illegal transactions, didn’t you? Aren’t you not supposed to facilitate this sort of thing? Isn’t that what it says in the rules?

Validators and the proof-of-stake shift

Though I’ve framed this above as a problem for miners, all the hand-wringing and infighting around Ethereum’s death pit is actually about the validators, not the miners. I started out the discussion by talking about it in terms of miners for reasons I’ll make clear shortly, but the fact is that the real fight is over the validators, and what they’ll do matters a lot.

For those who don’t follow the ins and outs of web3, Ethereum is presently on the verge of moving from a Proof-of-Work model, where miners compete to add new blocks to the chain, to a Proof-of-Stake model, where validators who have staked large amounts of ETH are the ones who add the new blocks.

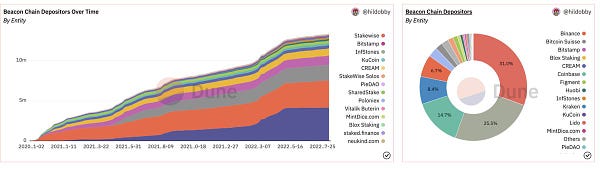

The shift from PoW to PoS (called “the merge” in Ethereum lingo) will also change the balance of power on the network, away from a relatively small group of powerful miners and mining pools to… well, whoever can stake the most ETH.

In the US, at least, centralized exchanges like Coinbase are sitting on the most ETH… actually, let’s just drop the pretense that this is not mainly about Coinbase. Coinbase is the 800lb gorilla in the world of US-based centralized exchanges (CEXes), so the big question on everyone’s is: will Coinbase’s validators add new blocks containing sanctioned transactions, or will the company try to take a pass on such blocks and let someone else, somewhere else (with less legal exposure) handle them?

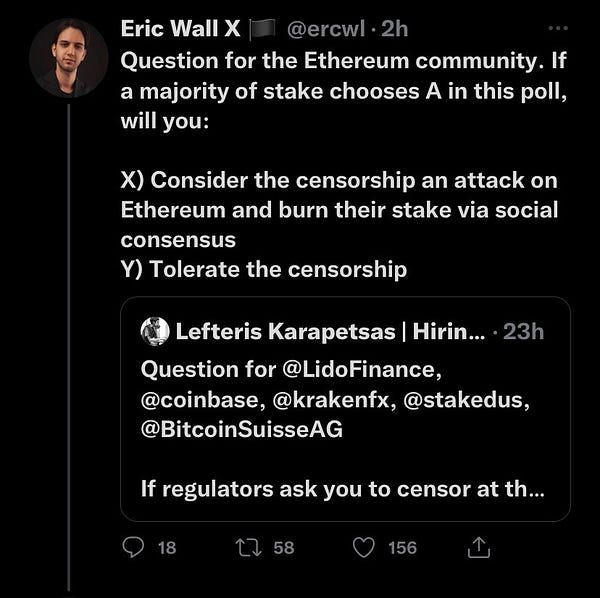

And the big answer on everyone’s mind is: no way will Coinbase validate a block with an illegal transaction in it, and risk the hammer of the US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (Fincen) coming down on it. It just seems very very likely that Coinbase will protect its execs and investors from Ethereum’s death pit by forcing any validators under its control to punt on all illegal transactions.

If we were just talking about PoW miners, then things would be bad enough for Ethereum. But ultimately, miners are big hardware pools that turn electricity into ETH, so the degree to which these entities are part of “the financial system” and are subject to US financial regulations — vs. just being some kind of internet plumbing, like a cloud provider or a telco — is still up in the air. Miners have historically had some shielding from liability for processing bad transactions, sort of the way telcos have had some shielding for carrying illegal or defamatory speech.

But the moment Ethereum moves to PoS and enters a world where adding new blocks is about who can collect and stake large amounts of a particular financial asset (i.e. ETH), then the job of processing transactions and growing the blockchain falls to entities that everyone agrees are quite firmly under the purview of US finance regulations and rule-making bodies. There really is zero ambiguity about who regulates the likes of Coinbase.

Furthermore, it’s the nature of the beast that such institutions are inherently risk-averse when it comes to which laws they break and which they obey. It’s one thing to steal hundreds of millions from customers, or to launder money for Mexican drug cartels — that’s all kinda naughty but basically forgivable. But nobody gives the finger to Treasury sanctions. Those laws are actually enforced.

What’s next for Ethereum?

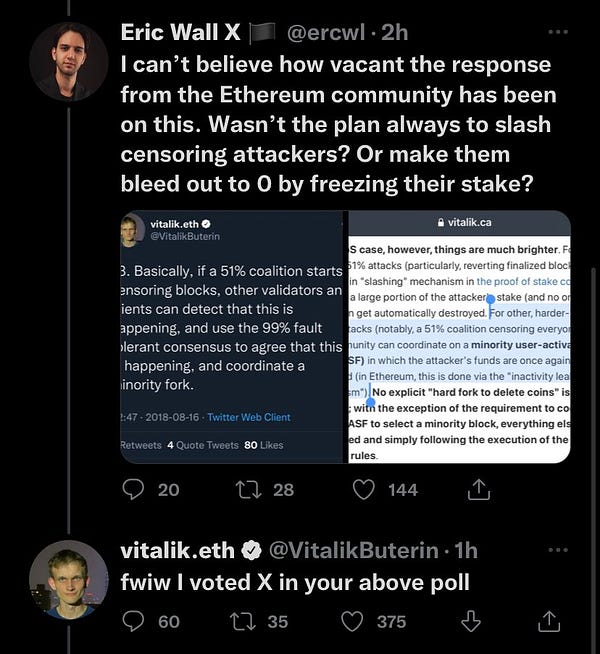

I’m going to refrain from speculating about how this could all shake out for Ethereum, and outsource such to my TL. The point of this post was to just flag for the crypto-adjacent how big of a crisis the community is facing right now, and how that crisis is related to the two main events everyone is talking about right now, i.e., the Tornado Cash sanctions and the PoS transition.

This is some kind of turning point for crypto, but it’s not yet clear in which direction.

Regarding the possibility of litigating these sanctions and making the problem go away (or at least giving everyone some breathing room), this is a critical piece. I was in a (sadly not recorded) recent Twitter Spaces with the authors of this, and it was excellent. The link above has a good summary of some of the better commentary they gave.

Please drop more good takes on the Ethereum Death Pit in the comments.

Ultimately, I think all this boils down to what I said in this thread:

Crypto will have to decide, and quickly, if it’s going to sell out to The Man or burn down the system. The time for pretending it can do both is almost up.