What Does It Mean to “Create” Something With Generative AI?

Just asking questions

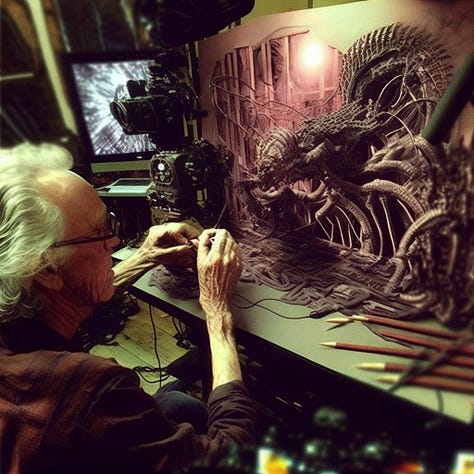

I’m in a Facebook group for AI-generated art, and recently in the comments on the stunning set of Midjourney-generated images shown above, a disagreement broke out over the fundamental nature of authorship in the age of generative AI.

On one side were a commenter and his allies who insisted the post’s author, Mike Wyatt of Defiled Existence Art, hadn’t actually “made” the images — that Midjourney had actually created them with the author’s text prompt. On the other side were members who marshaled various analogies about cameras, word processing programs, and other tools to insist Wyatt had not, in fact, misspoken when he had posted the image with the claim, “I made this in midjourney.”

I’ve seen versions of this debate break out on Reddit, Twitter, and other venues, and in fact I recently made my own contribution to it. (I’m embarrassingly overdue to jump in a second time in response to this opener from philosopher Joshua Hochschild. Soon!)

I don’t have an answer for this, and I don’t want to look for one in this post. What I want to do, instead, is survey the mess. Because when you look at it closely enough, you realize we’re in a truly strange moment where so much of the cultural and cognitive machinery we have around “creative work” is incredibly ill-equipped to deal with the massive change that’s already underway.

Words fail me

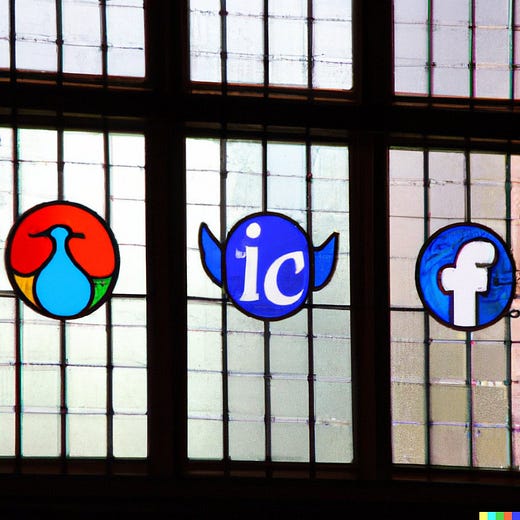

For some time now, I’ve been trying and failing to come up with an analog or precedent for what it’s like, as a working creative professional, to make something with a generative ML model. To understand what I’m getting stuck on, consider the following images I produced for a recent article on social networks.

The idea I was working with here was “social network lock-in.” I wanted something that evoked this lock-in concept, even very vaguely. At some point after browsing some other users’ image generations on PlaygroundAI, I hit upon the idea to do a stained glass window with social network logins. “Church,” “cathedral,” “structured community that’s easy to join but maybe harder to leave” — these are the kinds of concepts these images are supposed to evoke.

Because they were made with Stable Diffusion, these are my images in a legal sense — they don’t belong to whatever service or software I used to make them. I own the copyright to them, which is good because I came up with the idea for them, I crafted the prompt, I spent the money to do some generations, and I then selected the final images.

But are these images really mine? Well, they have the following qualities:

They didn’t exist before I generated (created?) them, but now they do.

They’re novel and interesting (at least to me), and have real “content” in that they communicate an abstract concept and are interpretable within the context of my article.

They were produced by me using some software on my laptop. In fact, for the version I actually used in the article, I did some cropping and tweaks with Pixelmator Pro.

I tried different concepts, prompts, and seeds until I got the image I wanted. In other words, I started with a vision in my mind’s eye and iterated toward it.

In my life and career, I have created many pieces of writing, many images for said writing (diagrams from scratch, photographs, logos, etc.), and even some music. Again, I’m a creative professional who works in multiple mediums, so I know what it’s like to create.

So I can say, based on experience, that these pictures feel like my images. As in, I kinda feel like I created them. But it’s weird because I also kind of feel like I just discovered them. It’s hard for me to put into words, but they exist in some limbo between “I, Jon Stokes, made this on my computer with some software tools,” and “I discovered these images out in nature or reality before someone else did, therefore they’re mine because I used some creative thinking to discover them first.”

(I’ve previously framed the two options referenced above — discovery vs. origination — as the Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives on not just machine creativity but human creativity. I still go back and forth on these two options, because both feel appropriate yet somehow inadequate.)

Anyway, I don’t yet have a good way to resolve any of this; I’m still thinking about it. Indeed, I’m so confused about this that I instinctively reached out to Mike Wyatt, the author of the text prompts that created the images at the top of this article, to ask his permission to use the images, without actually pausing to think about whether or not he really owned them.

But as we’ll see in the next section, the case I’ve described here is actually one of the easier ones. All this stuff gets a lot harder to untangle when you introduce other artists’ styles into the mix.

Ownership and style

The question of who really made an image gets further complicated in the many cases where an image is created in a specific human artist’s signature style by invoking that person’s name in the prompt. Now there are three possible candidates for who should really get the authorship credit for the image:

The person who supplied the prompt and seed

The ML model

The artist whose style was copied

You’ll probably object that nobody thinks the artist whose style was copied actually “made” that particular image, and that’s fair, which is why I framed the question as, “who should really get the authorship credit.”

There’s a sense that all three of these parties are responsible for the image, and indeed there’s a kind of norm emerging on the digital art scene for giving credit to artists whose names appear in prompts. Witness PlaygroundAI’s “Additional Credit” field alongside all the elements used to create the work:

This business of tossing some additional credit to someone whose name was used in a prompt is just a courtesy, though. Nothing about any of this “you’re using someone else’s distinctive art style” stuff is legally enforceable, nor should it be.

I’m not a lawyer, but I’ve covered the digital IP wars since they started up back in the late 90s, and to my knowledge copyright law doesn’t cover styles, themes, and similar abstractions. You can’t copyright a certain look (or a certain combination of flavors, or a style of music, or way of writing, etc.), no matter how closely that look or style is identified with your name as an artist.

Right now, your only recourse if someone rips off your signature style is to complain about it to the press and/or on Twitter, and hope the person who did the ripoff is suitably shamed and stops doing it.

None of this is naming and shaming going to work, though, in the new era of generative AI. Why? Because 99% of the people you might call out for stealing your style simply don’t care. 👈 This right here is very new and very, very weird.

Who benefits?

Here’s my best summary of the dilemma that generative AI presents to our culture:

Growing numbers of people are now using AI tools to generate high-quality, original artwork that they have vanishingly little ego, time, or money invested in. In fact, in most cases, the total investment in any of those three things is essentially zero.

Because these creators have almost nothing invested in the creation of the art, they aren’t expecting much in the way of ROI that might normally flow from getting real creator credit on a work.

But all of our society's infrastructure around artwork — norms, laws, language, expectations — is exclusively geared towards a world where the creation of high-quality art is an investment that should yield some payoff for the creator(s).

The bottom line: For the first time in human history, we’re about to reach a point where the vast majority of people who are personally (and in many cases solely) responsible for producing incredibly high-quality cultural objects do not care about getting credit for the creation of those objects and are not expecting any of the normal benefits — accolades, money, access to certain social circles, patronage, etc. — that have historically accrued to accomplished creatives.

What’s happening now with AI artwork is so weird and unprecedented that confusion is destined to reign until such a time as we settle on entirely new norms, laws, and concepts for “creativity” that fit this new reality.

Regular readers of this newsletter will recognize that there’s a vaguely can-openery type of thing going on here, i.e., we all need to settle into this new generative AI problem/solution pair to the point where we can think with it instead of about it.

*To clarify: Many artists who are getting into generative AI invest a ton of time in prompt engineering, in- and out-painting, cropping, remixing, and other aspects of AI art. I’m not talking here about these self-identified artists, though. I’m talking about the much larger number of people who are using these tools for purposes of entertainment or expediency — who just want an image that works for some purpose, and who are turning to AI instead of to Google Images, Unsplash, or a similar source.

Postscript: Cultural Appropriation

Despite my contempt for this entire concept and the types of people who typically cudgel others with it, “cultural appropriation” is probably the closest thing we have to a set of rules around who can copy styles from who and apply them to create new cultural objects.

(My view of “cultural appropriation” is pretty close to a militant atheist’s view of “sin,” i.e., at best the entire idea is really dumb, and at worst it’s actively malign and anyone who’s out in public talking about it as if it’s a real thing that anyone should care about is definitely up to no good.)

But apart from “cultural appropriation” discourse, we just don’t have a body of rigorous, legalistic thinking about “ownership” of styles, vibes, moods, and other I-know-it-when-I-see-it abstractions that AI will soon anyone easily apply to any cultural product. So it wouldn’t surprise me to see us looking to this discourse as we feel our way around these issues. And who knows, maybe I’ll eventually come to consider something in this discourse useful. Or not.

Excellent discussion as always, but I would argue that this shift has happened times and again, although here in a particularly salient form.

What I mean is that new technologies have rendered artisans obsolete, pushing for them to find meaning, and move to artistry.

Photo rendered obsolete portrait painters as a representation tool, is concomitant to an plethora of new painting movements that found meaning not in the technical resemblance of representation, but in the mood behind the strokes (Impressionism), or the decomposition of natural shapes in artificial shapes (cubism).

A tool rendering obsolete a human practice displaces it toward meaning, experiments and value addition.

This might be the beginning of what we are seeing there : what up to know was hard craftsmanship becomes mundane, and now an entire pan of craftsmanship is about to reinvent itself around new meaning.

Life will change and events will be influenced by artificial intelligence. Are we losing our humanity or enhancing it? Only time will tell.